The distinctive red diagonal cross on a white background known as st patrick’s saltire represents one of Ireland’s most significant yet complex heraldic symbols. Since 1801, this red saltire has formed an integral part of the union flag, representing Ireland within the United Kingdom’s national emblem. Named after saint patrick, Ireland’s patron saint, this symbol serves multiple roles in contemporary Irish and British contexts, from official government uses to cross community support initiatives in northern ireland.

Understanding the st patrick’s saltire requires navigating through centuries of contested history, political symbolism, and evolving cultural meanings. While some embrace it as an authentic irish flag representing the island’s heritage, others question its legitimacy as a genuine Irish symbol versus a British political construct.

What is St Patrick’s Saltire

St patrick’s cross, officially known as the saint patrick’s cross, consists of a red diagonal cross displayed on a white background. This x shaped cross design distinguishes it from the usual crosses found in Christian symbolism, creating what heraldic experts term a saltire formation. The flag’s red diagonal lines intersect to form the characteristic X pattern that has become synonymous with this irish context symbol.

The saltire serves as the official representation of Ireland within the british flag, where it combines with st george’s cross representing england and st andrew’s cross representing scotland. This tri-nation combination creates the familiar union jack design that has flown over the United Kingdom since the 1800 Acts of Union between great britain and Ireland.

As Ireland’s patron saint symbol, saint patrick’s saltire holds particular significance during saint patrick’s day celebrations and appears in numerous official emblems throughout Ireland and northern ireland. The flag proposed as a cross-community alternative offers a less politically charged option compared to either the irish tricolour or traditional Unionist symbols.

Historical Origins and Development

The formal adoption of st patrick’s saltire traces to 1783 when the Illustrious Order of St Patrick chose this red saltire flag as their official emblem. Lord Temple, serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, described the Order’s badge in correspondence as featuring “the Cross of St Patrick Gules” – the heraldic term for red coloring. This 1783 formalization marked the first official recognition of saint patrick’s saltire as a formal Irish symbol.

The addition to the union flag followed the 1800 Acts of Union between Great Britain and Ireland, when st patrick gules joined the existing crosses of st george and st andrew. This integration meant that for the first time, the irish parliament’s dissolution coincided with Ireland gaining symbolic representation in the unified national flag. The timing reflected broader political changes as Britain sought to represent ireland within its imperial structure.

However, the origins remain disputed among historians. Some scholars trace the red diagonal cross to the FitzGerald dynasty’s coat of arms, which featured similar heraldic elements. The powerful Anglo-Irish-Norman family wielded significant influence, with Gerald FitzGerald, the eighth Earl of Kildare, serving as viceroy under three English kings. Historical records from 1467 document accusations that he treasonably displayed his banners on Carlow Castle, suggesting the FitzGerald arms may have evolved into a broader Irish symbol.

Pre-1783 Irish Saltire Usage

Evidence of red saltires in irish context appears centuries before the formal 1783 adoption. Irish coins from circa 1480 featured small saltires flanking the Royal Arms of England, marking the earliest documented appearance. A 1576 map titled “Hirlandia” by John Goghe depicted a red saltire on a ship, though historians debate whether this represented an Irish vessel or a Spanish ship flying the Cross of Burgundy.

During the Irish Confederate Wars of the 1640s, military reports document irish brigade forces using ensigns with red saltires on gold fields. Preston’s Confederate forces at the 1645 Siege of Duncannon flew under saltire banners, while the irish brigade raised by the Earl of Antrim displayed gold flags featuring red saltires in their cantons. These military applications suggest the symbol held recognized significance in irish volunteer and rebel contexts.

Maritime evidence strengthens the pre-1783 usage case. A 1785 Waterford newspaper reported: “upwards of forty vessels are now in our harbour, victualling for Newfoundland, of which number thirteen are of our own nation, who wear the st patrick’s flag (the field of which is white, with a st patrick’s cross, and an harp in one quarter.)” This documentation proves that by 1785, irish shipping companies were using the white flag with red saltire as a recognized irish ensign.

European atlases from the late 17th and 18th centuries consistently depicted the red saltire on white as Ireland’s national flag. dutch flag book entries by Paulus van der Dussen (circa 1690) and the french army atlas “Le Neptune françois” (1693) labeled the design as “Ierse” and “Irlandois” respectively. These international recognitions suggest the saltire had achieved status as ireland’s de facto maritime flag before formal British adoption.

Design and Heraldic Specifications

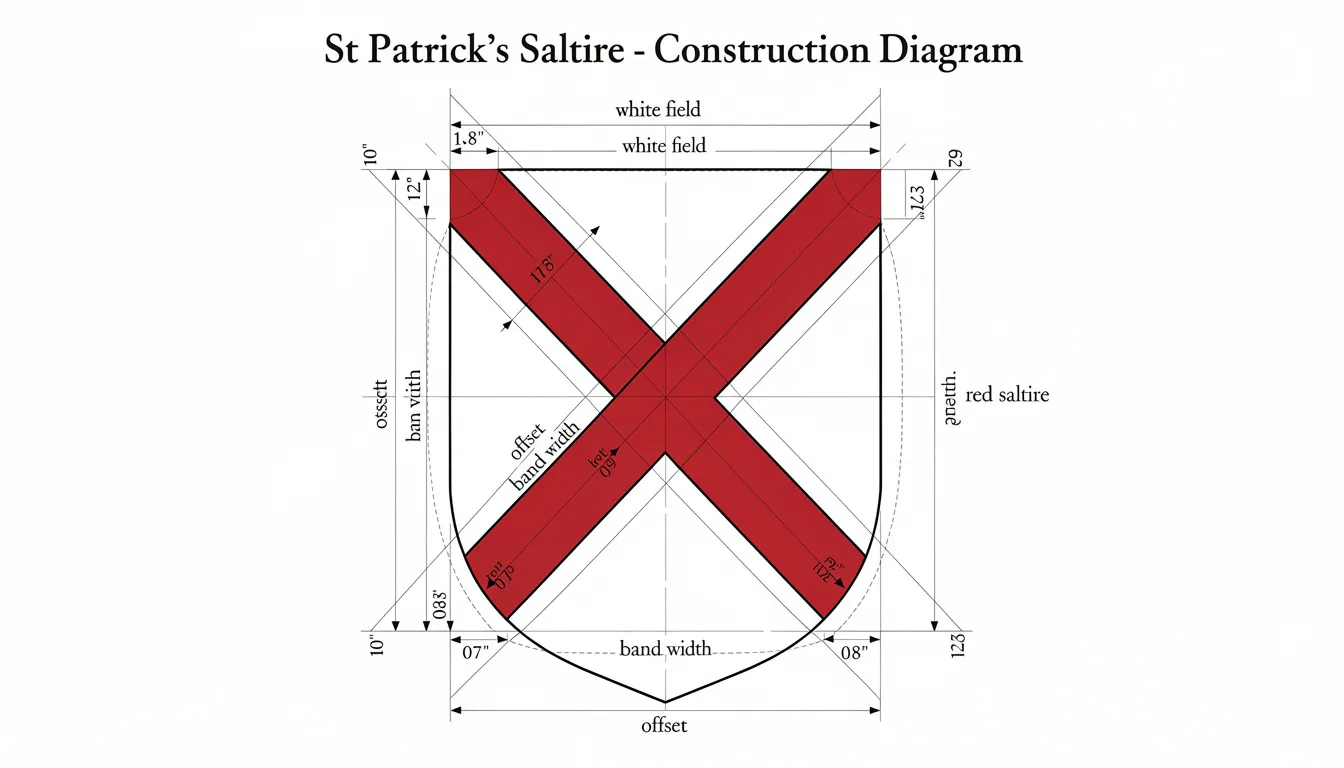

The st patrick’s saltire follows specific heraldic conventions in its construction and display. The design consists of red diagonal lines forming an X pattern across a white background, with precise angle requirements ensuring proper visual proportions. When displayed as an independent flag, the saltire maintains equal width for both diagonal elements, creating symmetrical visual balance.

Integration into the union jack requires more complex specifications due to the counterchanging with st andrew’s cross. The blue diagonal of Scotland’s patron saint intersects with st patrick’s red diagonal, necessitating careful positioning to maintain both symbols’ integrity. The correct display shows the white diagonal line positioned above the red in the upper hoist quarter – a detail that distinguishes proper union flag orientation.

Professional heraldic applications often include fimbriation – thin white borders around colored elements – when the saltire appears alongside other symbols. This technique prevents color bleeding and maintains visual clarity in composite designs. The royal college of surgeons ireland incorporates such fimbriation in their institutional arms, demonstrating proper heraldic practice.

Color specifications traditionally call for true red (gules in heraldic terminology) rather than orange or crimson variants. The white background should remain pure rather than cream or off-white, ensuring maximum contrast for visibility and symbolic clarity. These standards apply whether the flag appears in maritime contexts, official ceremonies, or institutional displays.

Official and Institutional Uses

St patrick’s saltire appears extensively throughout official British and Irish institutions, reflecting its recognized status as an irish symbol. The Police Service of northern ireland incorporates the saltire in their badge design, representing the force’s mandate to serve all communities. British Army regiments with Irish connections frequently display the cross of st patrick in their regimental colours, maintaining historical military traditions.

Trinity College Dublin, founded in 1592, features the saltire prominently in their coat of arms alongside other heraldic elements. The Church of Ireland Diocese of Connor includes saint patrick’s cross in their episcopal heraldry, while the roman catholic archdiocese of New York incorporates the symbol in recognition of Irish-American heritage. These ecclesiastical uses demonstrate the saltire’s acceptance across denominational lines.

Municipal heraldry throughout Ireland frequently incorporates variations of patrick’s cross. Cork city, Belfast, Westport, and County Fermanagh all feature saltire elements in their official arms. The widespread municipal adoption suggests local governments view the symbol as appropriately representing Irish identity without controversial political implications.

Educational institutions beyond Trinity College have adopted the saltire for institutional identity. queens university belfast displays the cross in their heraldic standard, while various secondary schools throughout Ireland incorporate saltire elements in their emblems. These educational applications help familiarize younger generations with the symbol’s visual appearance and historical significance.

Maritime and Transport Applications

The irish lights service, responsible for maritime navigation aids around Ireland’s coast, adopted the st patrick’s saltire as their official flag in 1970, replacing the previous use of st george’s cross. This change reflected growing Irish autonomy and the appropriateness of using an specifically Irish symbol for national maritime services.

Commercial shipping companies have historically used patrick’s flag for corporate identity. irish shipping, founded in 1941, flew house flags incorporating the saltire design. Irish Continental Line used similar saltire-based designs during their operational years from 1973-79, demonstrating commercial acceptance of the symbol as representing Irish maritime interests.

International maritime signal systems recognize the saltire pattern as the flag for letter “V,” conveying “I require assistance” or representing “Victory” in naval contexts. This standardization means the st patrick’s cross appears in signal flag sets worldwide, giving the Irish symbol global maritime recognition beyond its national applications.

Transport applications extend beyond maritime uses. Proposals for northern ireland vehicle registration plates suggested including the saltire as an optional symbol, similar to regional emblems used elsewhere in the United Kingdom. While not implemented, these proposals reflected ongoing discussions about appropriate symbols for northern ireland identity.

Symbol for Northern Ireland and Cross-Community Relations

In northern ireland’s complex political landscape, st patrick’s saltire offers unique potential as a symbol commanding cross community support from both unionist and nationalist communities. Unlike the irish tricolour, which many unionists reject, or the union jack, which many nationalists oppose, the saltire’s historical Irish roots combined with its incorporation in the british flag create possibilities for shared symbolism.

The 2012 Thames Diamond Jubilee Pageant demonstrated this cross-community potential when organizers chose to fly saint patrick’s saltire specifically to represent northern ireland alongside other regional flags. This decision acknowledged the need for symbols that could represent the region without alienating either community, showing practical application of the saltire’s bridge-building potential.

Down District Council has actively promoted the saltire for cross-community purposes, distributing flags before Downpatrick parades to encourage participation across traditional divides. Their initiatives recognize Downpatrick’s significance as saint patrick’s burial place and promote the saltire as an authentically Irish symbol deserving broader recognition beyond sectarian divisions.

Some unionist politicians and organizations have embraced patrick’s flag as validly representing Irish identity within the union jack framework. They argue the saltire demonstrates Ireland’s integral role in United Kingdom symbolism while maintaining distinctively Irish character. This perspective suggests the symbol could bridge constitutional differences by satisfying both Irish identity and union loyalty.

However, reception remains mixed within both communities. Some irish volunteer organizations historically complained about adopting what they perceived as a “Unionist fabrication”, while certain loyalist groups worry about symbols too closely associated with Irish nationalism. These tensions reflect broader challenges in flags of northern ireland and the region’s political and social scene.

St Patrick’s Day Usage and Cultural Significance

During saint patrick’s day celebrations, the saltire appears alongside or sometimes instead of the irish tricolour at parades throughout northern ireland and great britain. Parade organizers often view patrick’s flag as offering inclusive representation that welcomes participants from diverse backgrounds while maintaining authentic Irish symbolism.

In Downpatrick, near saint patrick’s burial place, local authorities promote the saltire during March festivities as a unifying symbol connecting all Irish people to their patron saint. These initiatives emphasize historical authenticity over contemporary political divisions, arguing that patrick’s cross predates modern constitutional debates and therefore transcends current controversies.

Some parade organizers in British cities have replaced irish tricolour displays with st patrick’s saltire to avoid controversy while maintaining Irish cultural celebration. This substitution sometimes generates criticism from irish organisations who view the tricolour as the proper national flag, creating ongoing debates about appropriate symbolism for diaspora celebrations.

Cultural organizations promoting Irish heritage increasingly recognize the saltire’s historical legitimacy and cross-community appeal. They argue that patrick’s day celebrations should embrace symbols that unite rather than divide, positioning the saltire as authentically Irish while accessible to participants regardless of political background.

The symbol’s appearance in saint patrick’s day contexts helps familiarize broader populations with its visual appearance and historical significance. This exposure contributes to growing recognition of the saltire as a legitimate element of Irish symbolic heritage deserving consideration alongside other traditional emblems.

Political and Cultural Contexts

The 1914 County Down irish volunteer movement faced internal controversy when members proposed adopting st patrick’s cross for their banners. Critics within the organization complained that using the saltire represented acceptance of a “Unionist fabrication” lacking authentic Irish roots. This early 20th-century debate established lasting questions about the symbol’s political legitimacy that continue influencing contemporary discussions.

During the 1930s, the irish volunteer complained when the Blueshirt movement adopted a variant featuring the red saltire on a yellow background rather than traditional white. The Blueshirts, led by Eoin O’Duffy, opposed republican politics and sought closer ties with European fascist movements. Their appropriation of patrick’s cross demonstrated how political movements could manipulate traditional symbols for contemporary purposes.

Modern Ulster separatist movements sometimes combine st patrick’s saltire with st andrew’s cross and the Red Hand of Ulster to create composite symbols representing their vision of Northern Irish identity distinct from both Irish republicanism and British unionism. These applications show how traditional symbols adapt to serve evolving political movements and identity concepts.

The Reform Movement, a “post-nationalist” pressure group in the Republic of Ireland seeking closer UK ties, incorporates patrick’s cross in their organizational badge. Their usage reflects arguments that Irish identity can coexist with British connections, positioning the saltire as evidence for historical Irish-British cooperation rather than inevitable conflict.

Contemporary Controversies

Contemporary debates about st patrick’s saltire reflect broader tensions within Irish political culture about authentic versus imposed symbols. Some irish nationalist critics argue the saltire represents British invention designed to create convenient Irish representation within imperial structures rather than genuine grass-roots Irish symbolism.

Conversely, some Ulster loyalist voices express concern about symbols too closely associated with Irish identity, preferring more explicitly British emblems. These perspectives create the paradoxical situation where patrick’s cross faces criticism from both communities it potentially could unite, demonstrating the complexity of symbolic politics in divided societies.

Academic historians continue debating the saltire’s origins and authenticity. michael casey suggests that while early Irish saltire usage predates formal British adoption, the specific association with saint patrick may represent later political construction rather than ancient tradition. Such scholarly discussions influence public perceptions of the symbol’s legitimacy.

The ni flag debate reflects ongoing struggles to find appropriate symbols for northern ireland that satisfy diverse community needs. While some advocate for patrick’s saltire as offering cross-community potential, others argue that no single symbol can bridge Northern Ireland’s fundamental constitutional divisions about national identity and political allegiance.

Related Irish Symbols and Similar Flags

Ireland’s traditional heraldic symbol, the gold harp on blue field, predates st patrick’s saltire by centuries and appears in official state contexts throughout Irish history. The harp remains the official symbol of the irish parliament and appears on Irish coins, representing continuity with pre-modern Irish identity. Unlike the saltire’s contested origins, the harp enjoys undisputed recognition as authentically Irish.

The irish tricolour, adopted during 19th-century nationalist movements, serves as the Republic of Ireland’s official national flag. Its green, white, and orange stripes symbolize the hoped-for unity between Catholic Ireland (green) and Protestant Ireland (orange), with white representing peace. The tricolour’s republican associations make it controversial in unionist communities, creating space for alternative symbols like patrick’s cross.

Celtic crosses and Brigid’s crosses offer additional distinctively Irish symbolic alternatives rooted in pre-Christian and early Christian traditions. These symbols avoid the political controversies surrounding state flags while maintaining clear Irish cultural identity. Some cultural organizations prefer these options for their undisputed historical authenticity and lack of political associations.

jersey’s flag features a similar red saltire design, though its origins remain unclear. Some historians propose connections to the st patrick’s saltire through FitzGerald family landholdings in both Ireland and Jersey, while others suggest jersey’s flag originated independently or through copying errors in 18th-century flag books. This parallel development demonstrates how saltire designs appeared across multiple jurisdictions within British influence.

The Cross of Burgundy, used historically by Spanish forces, sometimes appears confused with patrick’s cross in historical accounts. The burgundy cross features a ragged X design rather than straight diagonal lines, but similar coloring and basic formation create potential for misidentification in historical records. Understanding these distinctions helps clarify debates about early saltire appearances in Irish contexts.

Florida, Alabama, and Valdivia incorporate crosses resembling saltires in their official flags, though these derive from different historical traditions. These international examples demonstrate how X-shaped cross designs serve various political and cultural functions worldwide, providing context for understanding the st patrick’s saltire within broader heraldic traditions.

Conclusion

St patrick’s saltire occupies a unique position within Irish symbolic heritage, representing both historical continuity and contemporary possibility for cross-community understanding. From its mysterious pre-1783 origins through formal adoption by the Knights of Saint Patrick to its current role in northern ireland’s complex political landscape, the red diagonal cross on white background continues evolving as a living symbol.

The saltire’s incorporation in the union jack since 1801 demonstrates Ireland’s integral role within British political structures while maintaining distinctively Irish character. Whether appearing on irish lights vessels, in educational institutions like queens university belfast, or during saint patrick’s day celebrations, the symbol bridges historical periods and community divisions in ways few other emblems achieve.

Contemporary debates about the saltire’s authenticity and political appropriateness reflect broader challenges facing all symbols in divided societies. While some reject patrick’s cross as insufficiently nationalist or overly British, others embrace its potential for representing Irish identity within frameworks acceptable to diverse communities. These ongoing discussions ensure the saltire remains relevant to current conversations about identity, heritage, and political belonging.

Understanding st patrick’s saltire requires appreciating both its historical complexity and contemporary significance. As northern ireland continues developing shared institutions and cross-community initiatives, symbols capable of commanding respect across traditional divides become increasingly valuable. The red saltire on white background, with its centuries of evolution and adaptation, offers one pathway toward symbolic unity that honors Ireland’s complex heritage while building bridges toward shared futures.